A few weeks ago, I decided to pull my Metro app, Tunnels DC, from the App Store. After almost four years in the store, I thought it might be interesting to do a bit of a retrospectve on the app, what worked, what didn’t, and why I eventually removed it from sale.

Tunnels DC debuted on the App Store on November 9, 2010. I’d recently left a job, which gave me the extra hours I needed to finish the project after tinkering with it in my spare time. Back then I was commuting daily on the Metro, and although there were other apps that purported to show train arrival times, few were using Metro’s then-new API. Many of the other apps in the category also lacked much design polish. I felt that there was an opportunity for success with a well-designed app backed by official API data from WMATA itself.

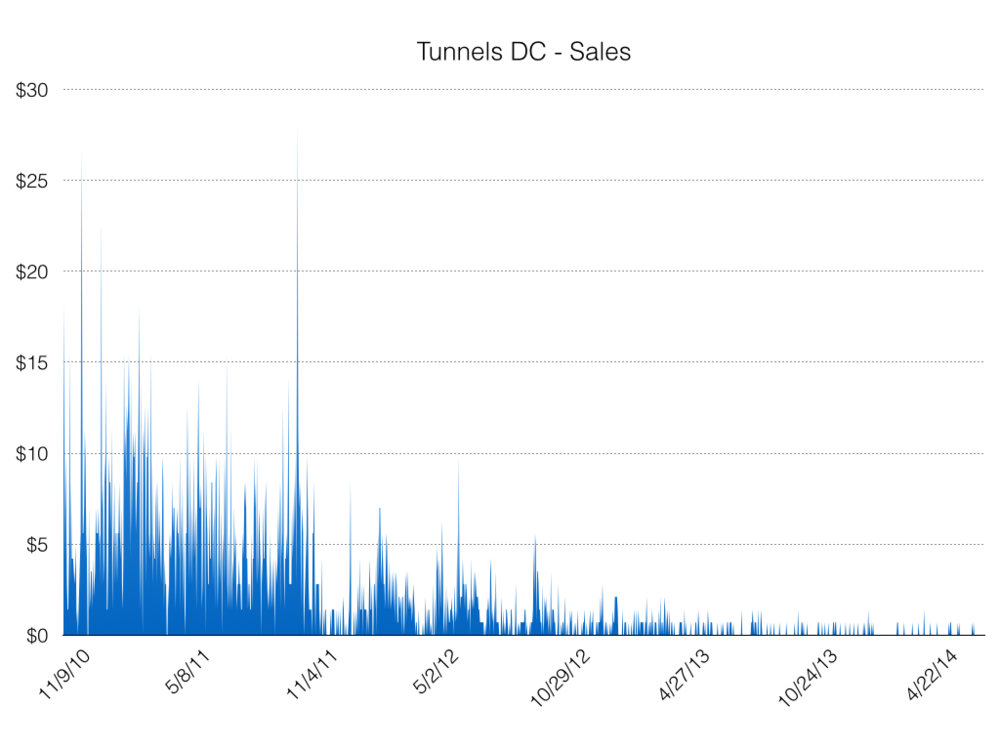

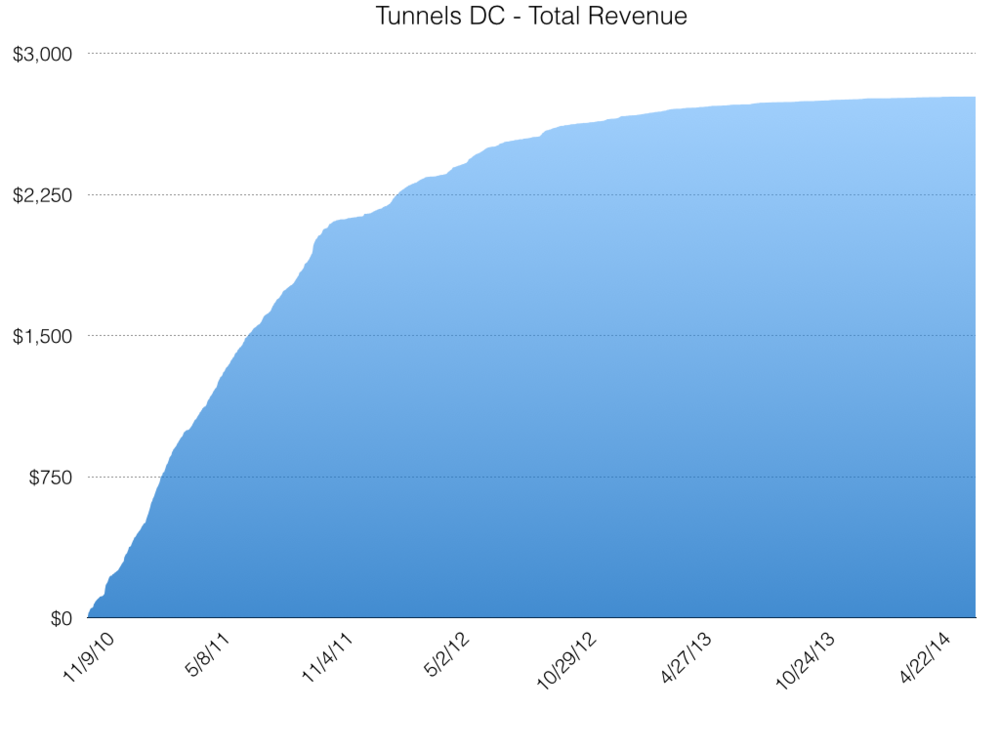

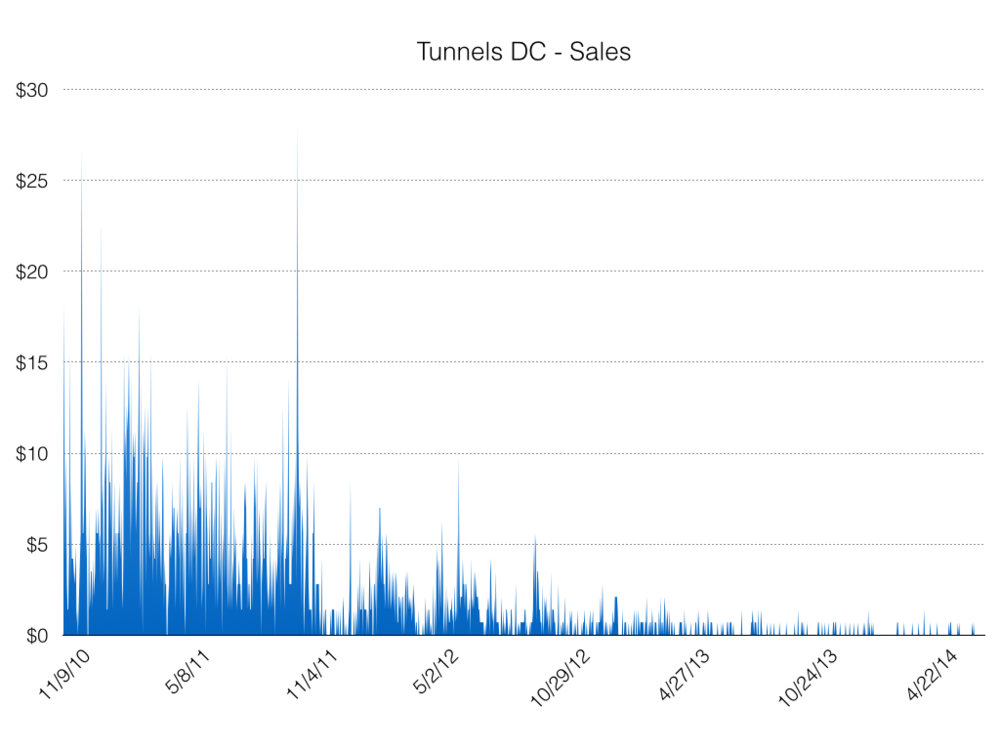

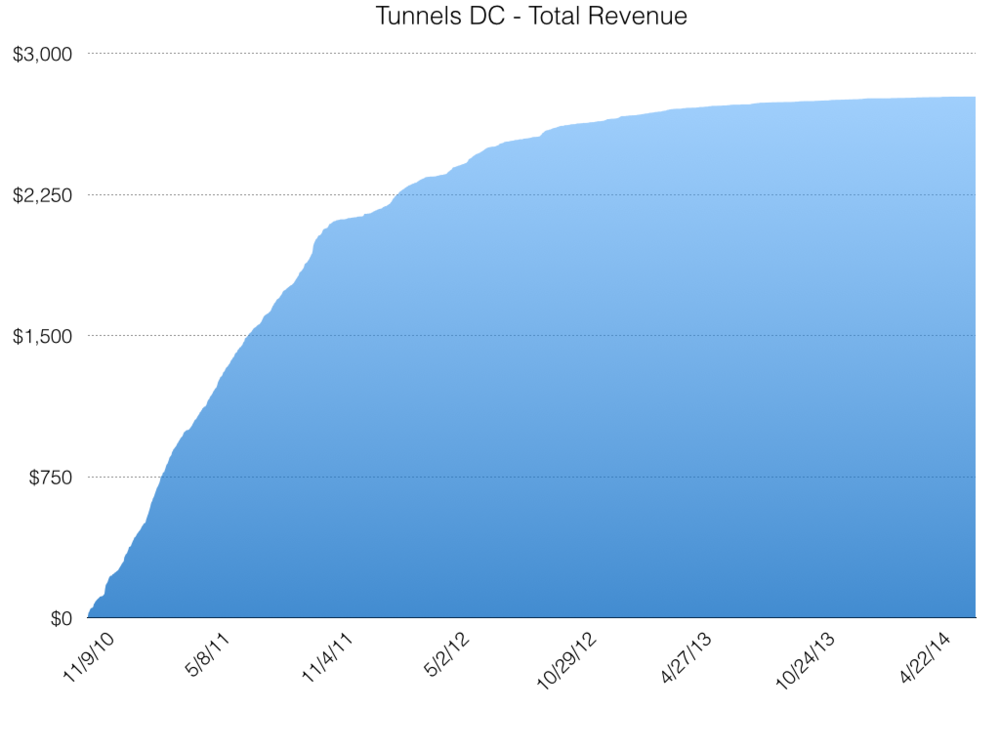

Unfortunately, Tunnels DC was never the commercial success I hoped it would be. Although I certainly didn’t expect to be making a full-time living off the app, I hoped that it would generate better sales than it did. Below are some charts showing the app’s revenue over time.

As you can see, the app’s best year was by far its first. After that, sales tailed off significantly. Even in the first year, the best sales days totaled less than $30. Most days were closer to $1-2. By the end of the app’s life, most days had no sales at all.

I attribute the app’s poor sales to two main factors:

Competition

This is probably the biggest reason the app wasn’t a success. In an increasingly crowded category, there just wasn’t much to set Tunnels DC apart. It wasn’t long before most apps were using the official API. Some supplemented that with additional data that wasn’t publicly available. Others clearly had very strong design teams working on them. Finally, a few apps were backed by large companies that could afford to promote their apps heavily. For example, DC Rider is published by the Washington Post, which is conveniently able to promote the app in their newspapers.

Tunnels DC also faced strong pressure on prices. Many of its competitors were free apps. Some of these had ads, while others were published by companies with other revenue streams. I considered making Tunnels DC free, but decided against it for three reasons:

- I wanted the app to pull its own weight. Although Tunnels DC never made a ton of money, it at least covered the annual cost of an iOS Developer Program membership that allowed it to be in the App Store. If the app were free, I’d be paying out of my own pocket to get it out into the world.

- I didn’t want to put ads in the app. I hate using apps with ads and would much rather pay a buck or two to get an app without them. Moreover, I wasn’t confident that ads would generate much revenue, even if app downloads increased somewhat.

- I guessed that a free app would come with increased support demands. I’ve heard a lot of developers talk about how free apps generate more negative reviews on the App Store, and more email from people demanding new or different features. I figured I’d rather stick to a low-priced paid app, even if it meant fewer downloads.

Limited Market

By its nature, Tunnels DC is only useful if you’re in the Washington, DC metro area. There’s no real reason for someone who lives elsewhere to buy the app. As such, the pool of people who might even consider buying the app is relatively small.

Limited Investment

Given the app’s modest download numbers, I hesitated to put a lot of time into adding features. Realistically, it’s unlikely I would have gotten a very good return on my time investment. If I’m being honest, I also didn’t have a ton of ideas for ways to expand on the concept. In such a highly competitve app market, I needed to come up with a good way to differentiate my app from others. Since I failed to come up with strong new feature ideas, I decided to spend my time elsewhere.

Ultimately, my decision to pull the app from the App store was a result of poor sales numbers. By this summer, downloads had decreased so much that the app didn’t seem worth even the minimal level of support it required. I was also given a push by the start of service on Metro’s new Silver Line. As the Silver Line launch date approached, it was unclear that the API would support it. A tip from someone familiar with the situation confirmed my suspicion that the API is not high on WMATA’s list of priorities. Although the API did eventually gain support for Silver Live trains, the uncertainty surrounding it was enough to tip the scales in favor of removing Tunnels DC from sale. Although I’d almost certainly have done so sooner or later in any event, the issue with data reliability served as a prompt to pull the trigger.

Tunnels DC was never a project designed to pay the bills. Nonetheless, it does offer some lessons for next time. Foremost among these are:

- Pick a good market. Make sure it’s big enough to support sustained app sales.

- Have strong features that set your app apart. This seems obvious in retrospect, but I think it’s an easy trap to fall into. The more crowded the category, the more the app needs to differentiate itself from the competition.

I have a couple of app ideas in the works, so there should be an opportunity to put these lessons into practice sooner rather than later. Stay tuned.